As health communicators, we spend a lot of time encouraging people to avoid health risks. And often, the first step is convincing them that there is a risk in the first place!

You may be tempted to tell them all the scary things that could happen if they don’t change their ways. (Don’t be too accommodating to cats, or they may… dun dun dun… TAKE UP RESIDENCE ON YOUR HEAD!) But we know that fear appeals are tricky to use effectively.

So what’s a health communicator to do? Fear not! The Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM) is here to save the day. The EPPM, developed by Dr. Kim Witte, explains that health risk messages tend to get people thinking about 2 things: threat and efficacy.

Perceived threat describes how people think about a particular health risk. It has 2 parts:

- Perceived severity (“How bad is cat head, really?”)

- Perceived susceptibility (“What’s the chance of me personally getting cat head?”)

Perceived efficacy describes how people think about behaviors to prevent the health risk. It also has 2 parts:

- Perceived response efficacy (“Does keeping your hair wet at all times really prevent cat head?”)

- Perceived self-efficacy (“Can I personally go through life with eternally wet hair?”)

According to the EPPM, how we perceive threat and efficacy determines our health behaviors.

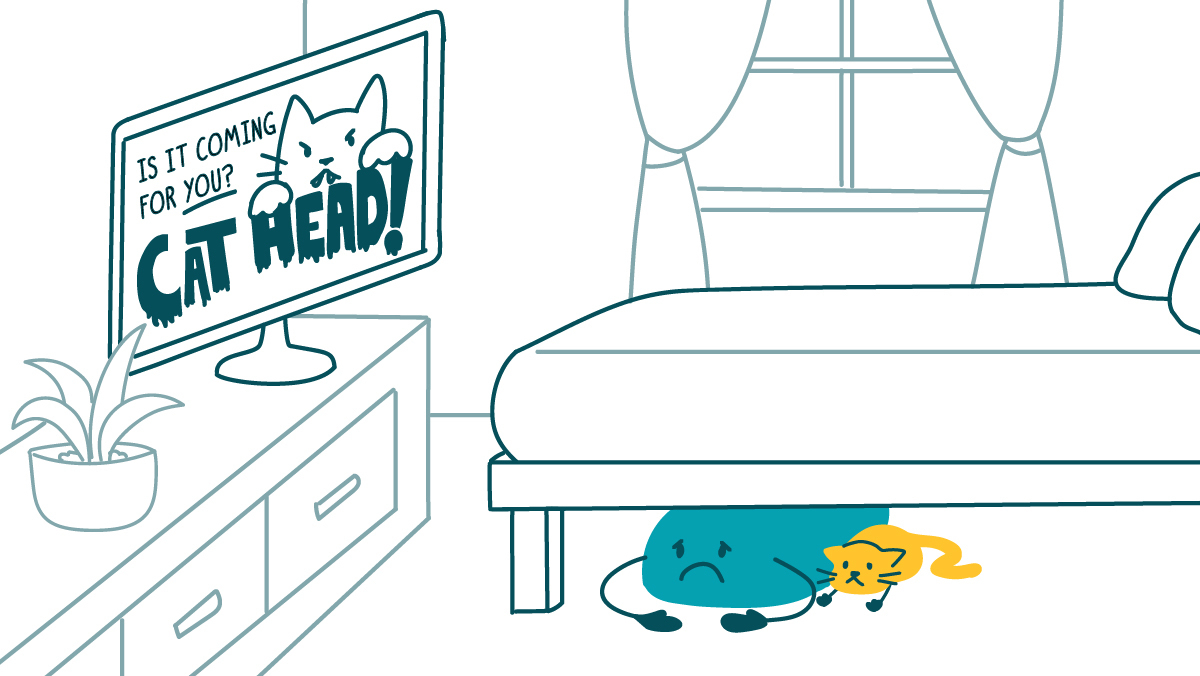

How does this work in practice, you ask? Let’s say you try a fear appeal. You make a scary TV commercial that shows a person with a truly dire case of cat head. At the end, in big spooky font, the commercial says: “CAT HEAD: IS IT COMING FOR YOU?”

The first person who sees your commercial thinks, “How unfortunate for that poor fellow. But my cat just isn’t the clingy type, so clearly cat head can’t happen to me.” They don’t perceive that the threat is relevant to them (low perceived susceptibility), so they don’t take any action to avoid it.

The second person who sees your post thinks, “Oh no! I, too, have a head and a cat. So I could catch cat head any moment!” You got their attention — but now they’re too terrified to take any preventive measures (sky-high perceived severity and susceptibility). Instead of taking action, they choose to hide under the bed.

What went wrong here? According to EPPM, the key to an effective health risk message is a delicate balance between perceived threat and efficacy. Fear can be a powerful motivator, but we don’t want to motivate people to hide under the bed. We want them to feel that the threat is personally relevant to them, but also feel confident that they can take steps to prevent it.

So let’s try this message again, with a better balance of threat and efficacy: “Anyone who treats cats with too much courtesy is at risk for cat head. But the good news is that you can protect yourself by keeping your hair cold, wet, and inhospitable to cats. Ask your doctor if wet hair is right for you.”

We don’t know about you, dear readers, but we’re feeling more in control of our cat head risk already.

The bottom line: Take a cue from the Extended Parallel Process Model — balance threat and efficacy to help your audience avoid health risks.

Browse recent posts