Here at We ❤ Health Literacy Headquarters, we’re always looking for ways to build stronger connections with our audiences. And using the right voice and tone is one way to forge that connection! So this week, we’re sharing tips to help you identify a clear voice and tone in your health writing.

First, a little refresher on what voice and tone mean. Voice is constant. It’s a key part of your identity — an expression of personality that comes out through your writing. In the corporate world, it’s often called “brand voice,” but it’s not just for the Apples and Fords. Whether you work for a Fortune 500 company, a government agency, or a community nonprofit, you need a consistent voice.

But what is voice, exactly? Think about how you can recognize your favorite singer even if you’ve never heard the song before — that’s because their voice is distinctive across different songs (or in our case, health materials!).

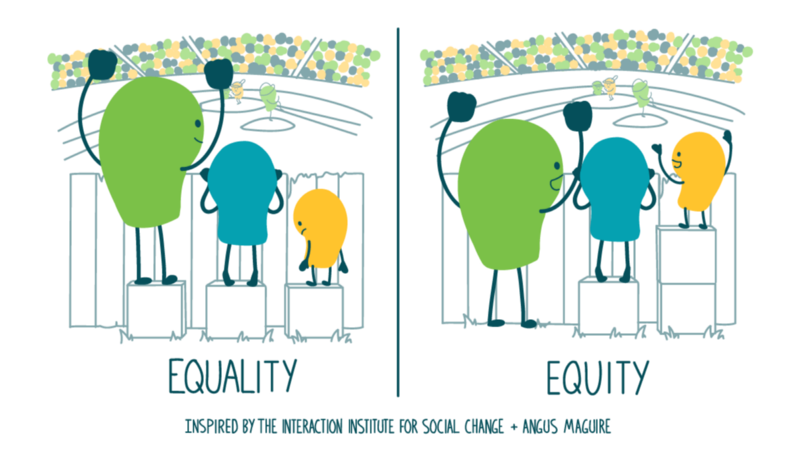

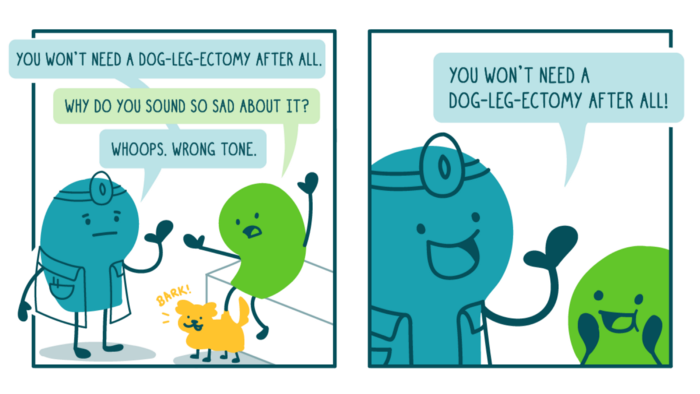

Tone, on the other hand, is situational. It varies based on the specific topic, the context, and your audience’s likely emotional state. So while voice stays the same across a website or campaign, tone may change slightly from page to page or tweet to tweet.

Think of it this way: No matter who you’re talking to, you’re still yourself — that’s your voice. But you wouldn’t talk to your best friend the same way you’d talk to your boss, or your sworn enemy, or the teller at your bank — you vary your tone based on who you’re talking to and what the conversation is about.

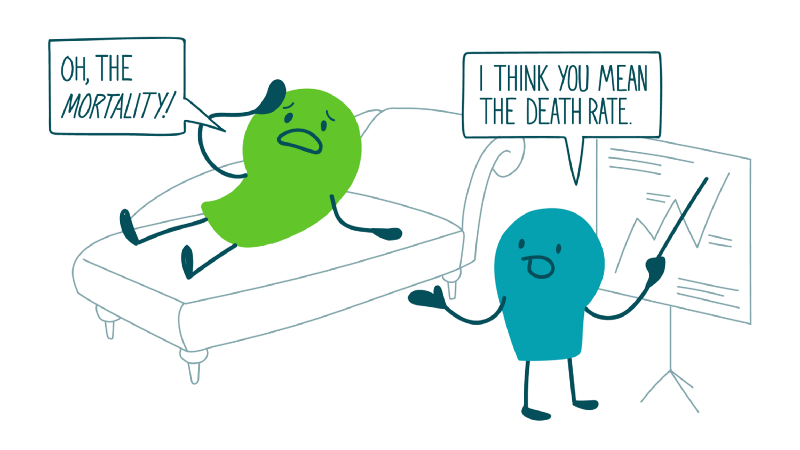

So, how do you figure out the right voice and tone to use? We often define voice and tone as a series of adjectives — like “friendly, compassionate, and sincere.” And to really bring out the nuance, it can be helpful to think about what your voice or tone is and what it isn’t. For example, you might describe your health communication campaign’s voice as:

- Optimistic, but not naive

- Friendly, but not overly familiar

- Informational, but not dry

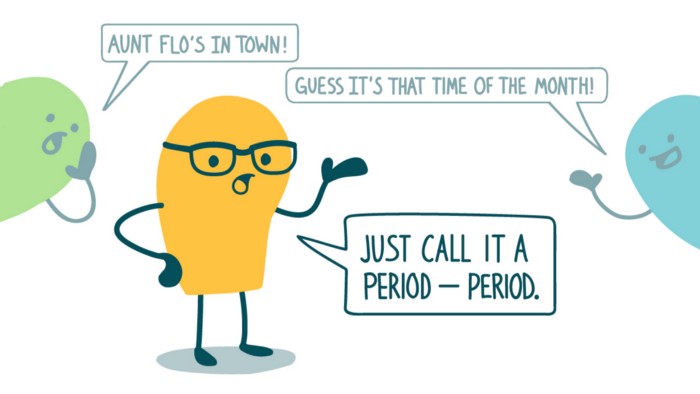

When it comes to tone, you’ll need to get more specific. What’s the health topic at hand? What is the audience likely thinking or feeling while reading about it? For example, a playful, quirky tone might be perfect for sharing general healthy eating tips, but it wouldn’t be a good fit in nutrition tips for people starting chemotherapy. In that case, the tone might be:

- Motivating, but not overly upbeat

- Comforting, but not patronizing

- Serious, but not dire

The bottom line: To build a stronger connection with your audiences, think through the voice and tone of your health comm materials before you write.