Here at We ❤️ Health Literacy Headquarters, we’re all about empowering people to make informed health care decisions. We know that shared decision making — when patients and doctors work together to identify the best treatment plan — promotes positive health outcomes. But even people with plenty of skills and experience navigating health care sometimes leave the doctor’s office feeling confused, defeated, or unheard.

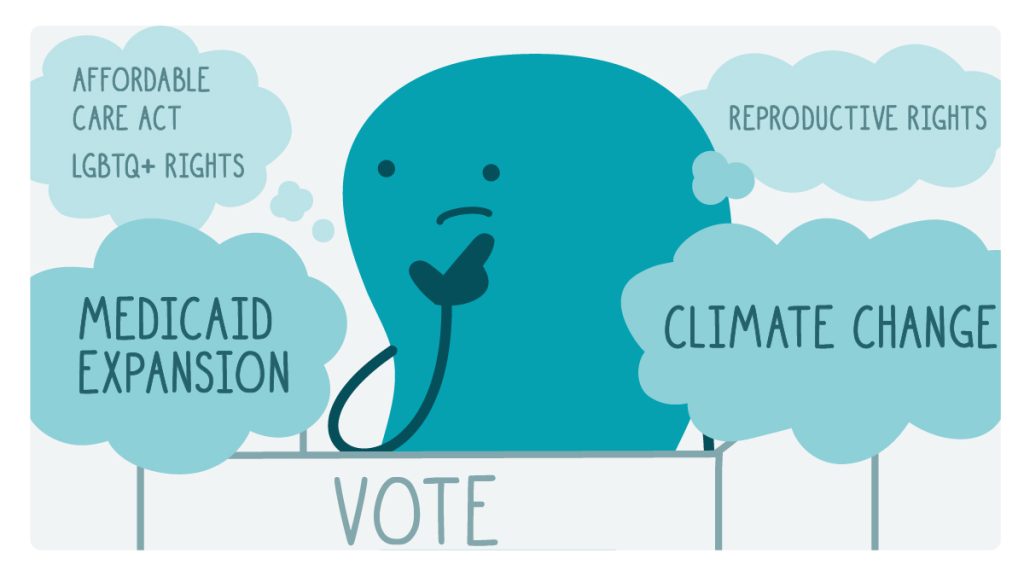

It’s easy to understand why. Doctor’s appointments are often rushed — and when we’re not feeling well, our capacity to interpret complex health information and respond in real time takes a nosedive. For people who’ve experienced trauma, it’s even harder to access those skills in the moment. And we know that people of color, disabled people, and LGBTQ+ people are more likely to experience bias and discrimination in the health care system.

The good news is that there are steps people can take to advocate for themselves at doctor’s appointments. Preparing questions ahead of time is one way to reduce pre-appointment anxiety and make the most of a short visit. Learning a few scripts, or basic phrases, to use in conversation with a doctor can empower people to ask questions, set boundaries, and advocate for their needs — even when they’re feeling overwhelmed. Here are a few self-advocacy scripts to share with your audiences, along with our thoughts on why they can be effective.

“What information will this test give us?” To make informed decisions about testing (which can be time-consuming, uncomfortable, and expensive), patients need to understand what information the test will provide — and how doctors will use that information. Encourage your audiences to ask questions about any test their doctor recommends.

“How will this treatment help me?” People are more likely to follow guidance if they understand how the treatment will improve their quality of life. Discussing the intended outcome also helps patients understand what to expect, so they can assess whether a treatment is “working”— and revisit the treatment plan with their doctor if it’s not.

“Are there other treatment options we can consider?” Remind your audiences that they don’t have to accept the first treatment plan presented to them. Encourage readers to learn about their treatment options and discuss the pros and cons of each one with their doctor before making a decision.

“What could happen if I don’t get this test or treatment?” With health care costs on the rise, it’s helpful to know if a doctor’s recommendations are nice-to-have or need-to-have. By addressing this question head-on, patients can clarify their options — and learn about the risks of not pursuing a specific test or treatment.

“Is there anything I can do to manage this side effect?” Encourage readers to discuss any side effects they’re experiencing with their doctor. In some cases, there are simple steps patients can take to make side effects more manageable. And if side effects interfere with everyday life or cause new health issues, a doctor may be able to recommend other treatment options.

“I’ve found I’m healthier when…” This simple phrase can be a powerful way for patients to set boundaries by clearly expressing what they do or don’t want. For example: “I’ve found I’m healthier when I don’t focus on the number on the scale. Please don’t check my weight when I come in for my next appointment.”

The bottom line: Many people struggle to speak up for themselves at the doctor’s office. Sharing scripts, or basic phrases, to use during doctor’s appointments can help your readers advocate for their needs.

Copy/paste to share on social (and tag us!): Speaking up for ourselves can be tricky — especially during health care visits. CommunicateHealth offers simple scripts health communicators can share to help people advocate for their needs at the doctor’s office: https://communicatehealth.com/wehearthealthliteracy/how-can-health-communicators-support-patient-self-advocacy/ #HealthCommunication #HealthLiteracy #HealthComm

![A late-night talk show host doodle sits at a desk labeled “Voices From the Field.” On the wall behind them, a banner says “Health Literacy Month Edition!”]](/wp-content/uploads/WHHL-doodle-2024_10-17-1024x576.jpg)