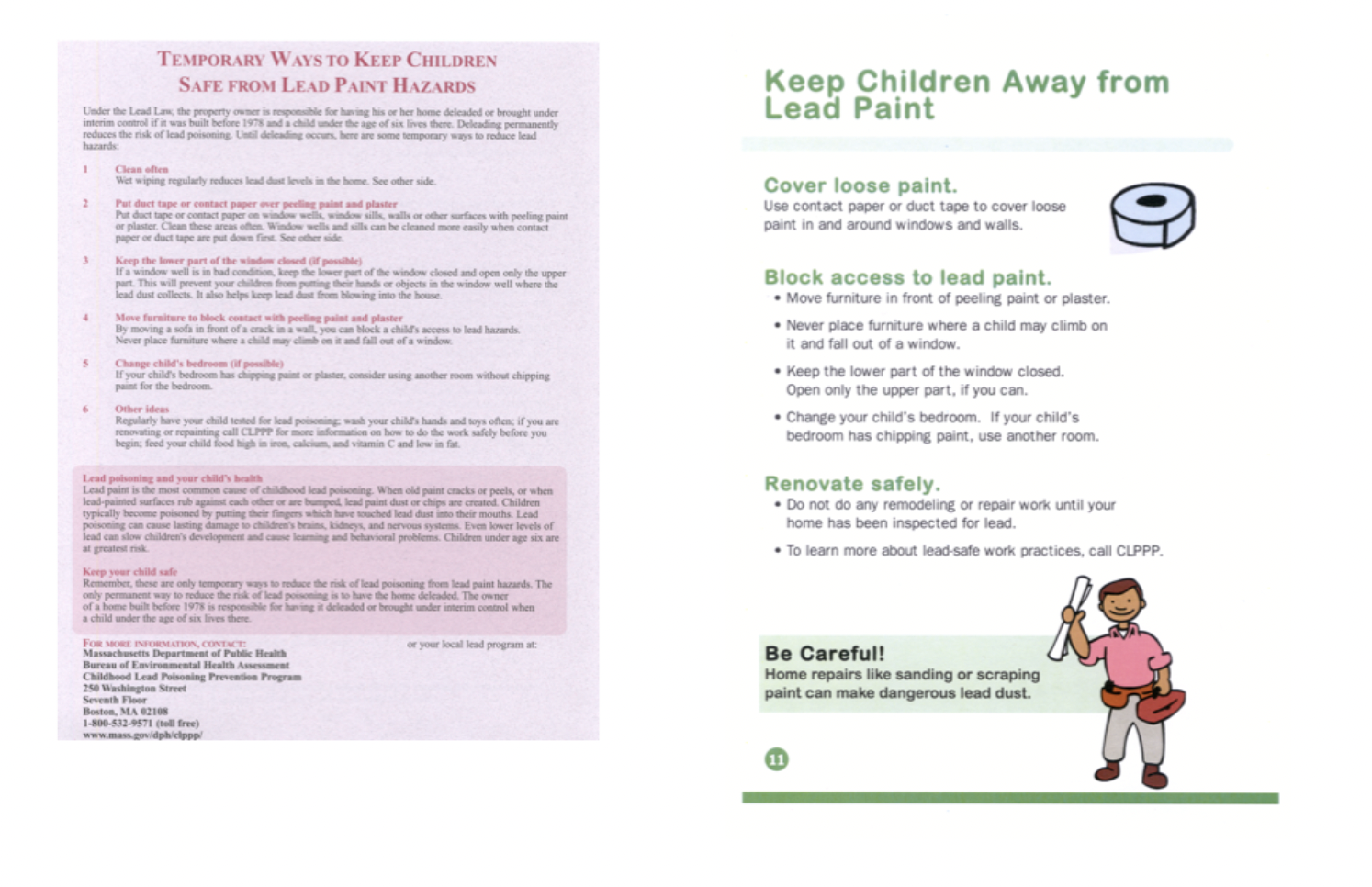

When budgets get tight, user testing often ends up on the chopping block. But there’s a way to do it on the cheap when more formal testing isn’t an option. Take it to the people — do a pilot test!

Pilot testing allows you to develop or improve your health materials together with your priority audience. Let’s face it: All materials have problems (some more than others). These problems may not be obvious to you, but your users will always spot them. Use this to your advantage.

You can do pilot testing with just about anyone. Ideally, you have 3 to 8 people from your priority audience test your materials. If that’s not possible, settle for the “1 is better than none” approach. The feedback of a single coworker not involved with your project is better than nothing. Parents and grandparents are often good to test with, too — plus it counts as a phone call!

Although your results may not be generalizable in the academic sense, even a test or 2 will catch usability issues that you likely wouldn’t have caught on your own.

We like to pilot test anywhere people wait: clinic waiting rooms, community centers, libraries, adult education centers, campus student centers. And recruiting is pretty easy as long as you’re prepared to hear about 10 “no thanks, I’m in a rush” responses for every 1 person who stops to talk with you.

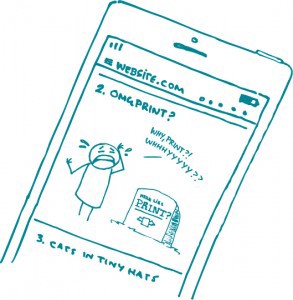

The questions you ask will depend on what you’re testing, but here’s our greatest hits collection:

- What catches your eye?

- Who do you think this material is designed for?

- Tell me in your own words what this is trying to say.

- What is it telling you to do?

- What do you think of the pictures? Do these people look like anyone you know?

- Do you think you could do what this material is suggesting?

- Do you think people will take any of these steps after reading the material?

And, we’d like to give a friendly reminder to always get the needed organizational approval for testing (e.g., Institutional Review Board (IRB) clearance). Small pilot tests are often exempt, but it’s best to check before you start.

The bottom line: Pilot testing can be an easy and inexpensive way to get feedback from your audience. Try it with your next project.